The explosion in the development of AI (Artificial Intelligence) in recent years is comparable to the explosion of the Internet 20 years ago and, more recently, the rise of social networks along with the way websites and these same networks use the data of their subscribers. Back then, the question arose: what do these sites do with the data I provide them? Are they even supposed to keep this data forever, risking leaks in the event of a cybersecurity incident? Is this a legitimate use? Are my data used to make money?

In this context, the European Union enacted the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Similarly, for AI, questions arise about its use, especially if it involves systems embedding AI whose operation may affect people. Due to the potential risks posed by AI, the European Union enacted the Artificial Intelligence Regulation.

This text was published in August 2024 in its final version, with implementation spread over time, the first two chapters being applicable since February 2, 2025. Who is concerned? Every European citizen, to varying degrees! The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of this regulation to give readers an initial understanding of how this regulation may apply to them.

1. THE DIFFERENT CATEGORIES OF AI & RAISED AWARENESS

1.1. PROHIBITED AI

Certain use cases are outright banned: to roughly summarize, if AI were used to manipulate people, exploit their weaknesses, categorize groups of people, build databases in advance, perform biometric processing without safeguards, it would be prohibited under this regulation. In a few keywords, the types of prohibited AI include:

- Manipulation aimed at distorting people’s behavior

- Exploitation of vulnerable persons due to age, disability, socio-economic status, etc.

- Classification of people based on their social behavior or characteristics leading to harmful treatment outside the context of that classification. A typical example would be delegating to an AI system the calculation of a “social credit” score

- Assessing the risk of criminal offenses solely based on profiling individuals. In other words, an AI version of the movie Minority Report

- The creation in advance of biometric recognition databases by extracting images from public spaces (Internet, television)

- Recognition of emotions of people in workplaces and educational settings, except for medical or security use

- Creation of biometric databases inferring race, political opinions, beliefs, sexual orientation. The only exception here concerns databases created within a legal framework

- Real-time biometric identification systems in public spaces. However, the regulation provides exceptions to this ban, notably for searching victims, preventing threats (e.g., Vigipirate and sensitive public events), and locating persons subject to criminal prosecution, depending on the severity of such prosecutions.

To summarize, prohibited AI systems are those considered illegal or immoral, those making decisions that should be human-made, or those constituting pre-compiled databases. In the latter case, we can see the influence of GDPR on this regulation. The exceptions mentioned above are strictly regulated and subject to validation either by the European Union or by the authorities of the member states.

1.2. HIGH-RISK AI

- Biometric systems, insofar as their use is authorized by the EU or the law of member states

- Critical infrastructure: road traffic, water, gas, and electricity management, for example

- Education or vocational training

- Employment and workplace management

- Access to essential services, whether private or public. The regulation specifically mentions healthcare and assistance services, financial services related to creditworthiness, life/health insurance, and emergency services

- Law enforcement services for detecting victims of crime, assessing the reliability of evidence, evaluating past behavior, and even profiling individuals — but strictly within a framework already specified by other EU regulations

- Migration flow management

- Support for judicial processes and democratic processes

- Products listed in Annex I of the regulation, namely: machinery, toys, recreational craft, protective equipment in explosive atmospheres, radio equipment, pressurized equipment, cable installations, personal protective equipment, gas appliances, medical devices, civil aviation, vehicles, marine equipment, and the railway system. Broadly speaking, all systems and equipment that are inherently risky, where the use of an AI system is plausible, and that are already subject to EU directives or regulations.

1.3. AI WITH SYSTEMIC RISK

Due to the nature of AI systems, it is possible that these systems are designed to be adaptable and therefore are not developed for a specific purpose or function. These are referred to as general-purpose AI systems.

Unlike the AI systems described in the two previous sections, where the level of risk is defined by the AI’s use or domain, general-purpose AI systems are considered risky based on circumstances. Indeed, the regulation defines a general-purpose AI as posing potential risks if it meets one of the following criteria:

- Indicators or benchmark criteria signal that this AI has high-impact capabilities (for example, the number of deployments on smartphones in the population)

- Its capabilities are sufficiently high: number of parameters, size and quality of data processed, amount of computation used for model training, input and output formats of the model, its ability to self-adapt to new tasks, and the size of the AI’s target market.

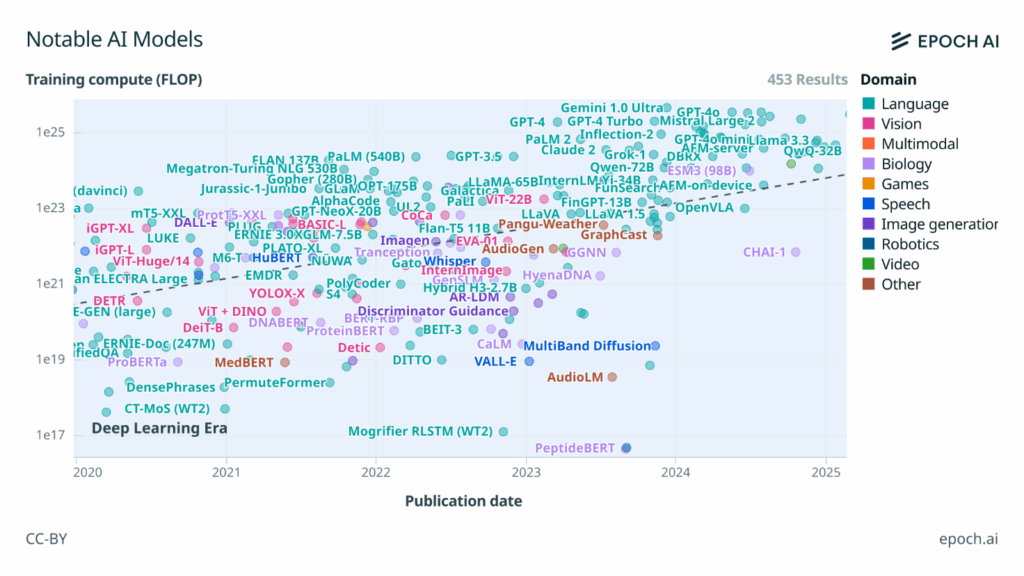

It is noteworthy that the regulation does not specify any numerical thresholds for these capabilities, except for the training computation amount, which is set at 10²⁵ floating-point operations. As of the time of writing, few AI models reach or exceed this threshold, corresponding mostly to those most often reported in mainstream media (see the graph below ranking the amount of operations used to train various AI models since 2020).

1.4. REMARKS

2. THE ROLE OF THE AI REGULATION

This regulation aims to establish a framework for the development of AI-based tools, their marketing, and their use, hence the necessity to precisely define which AI is concerned, as explained in the previous section.

Its goal is to protect any European citizen who may be affected by AI, particularly regarding their health, safety, and fundamental rights. It also aims to maintain order (in terms of law enforcement) and protect the environment.

A question that may arise at this stage about applicability is: what if a European citizen works for a non-European group, and this group internally uses AI tools that remain outside European territory (thus no distribution within the EU)? Does the regulation apply? The answer is yes: protecting the European citizen is the core objective of the regulation, just as GDPR is in the context of personal data management.

Alongside this, even if no European citizen is affected (AI system for export outside the EU), from the moment an AI is developed within the EU, the regulation also applies.

3. ROLES, RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS

- Providers, e.g., a company developing software chatbots

- Deployers, i.e., AI users with a specific purpose

- Manufacturers, who integrate AI systems into their products

- Importers, who place AI systems on the market

- Notified bodies, organizations responsible for assessing compliance with the regulation

- Notifying authorities, national agencies responsible for enforcing the regulation, through the implementation of dedicated national procedures and the designation of notified bodies

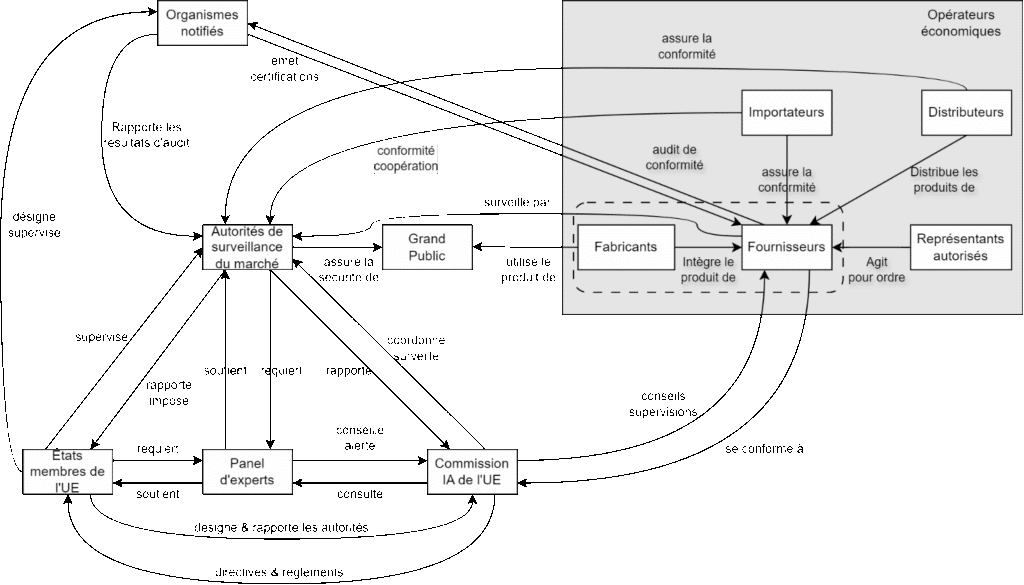

This diagram is supplemented by the two following tables: one summarizing the obligations of roles close to AI design, and the second summarizing the obligations of entities responsible for AI oversight.

The first table lists, for each row, the obligation and, for that obligation, which of the AI operators in each column has an identified role. For example, authorized representatives are required to keep for 10 years the contact information of the AI providers they represent.

1st table

| Type of obligation | Providers | Authorized representatives | Importeurs | Distributors | Providers / Manufacturers |

| Compliance with requirement | Ensure | Verify | Ensure | Verify | Ensure |

| Contact information | Indicate | Keep 10 years | Indicate | – | – |

| Quality management system | Maintain | – | – | – | – |

| Documentation | Prepare and archive | Verify and keep (10 years), provide access | Verify | – | Apply, assess data protection |

| Logs | Keep | Provide access | – | – | Keep |

| Compliance audit | Ensure | Verify implementation | – | – | – |

| EU declaration of conformity | Prepare | Verify | Verify | Verify | – |

| CE marking | Affix | – | Verify | Verify | – |

| Registration obligation | Comply | Ensure | – | – | Comply (if the deployer is a publmic institution |

| Corrective measures | Take | – | – | Take | – |

| Informations to authorities | Provide | Provide | Provide | Provide | Provide |

| Authorities | Cooperate | Cooperate | Cooperate | Cooperate | Cooperate |

Employees/ End users | – | – | – | – | Inform |

| Use (human oversight) | – | – | – | – | Monitor |

| Law enforcement | – | – | – | – | Request authorization |

2nd table

| Obligations | EU IA Commission | Notifies bodies | Market surveillance authorities | EU member states |

| Guidelines | Develop | – | – | – |

| Standardization requests | Issue | – | – | – |

| Compliance | Monitor | – | Monitor | – |

| Assessments | Conduct | – | Conduct | – |

| Technical support | Provide | – | – | – |

| Confidentiality | Ensure | Ensure | Ensure | Ensure |

| Commission | – | Refer to | Refer to | Refer to |

| Other authorities | Cooperate | Cooperate | Cooperate | Cooperate |

| Regulatory sandboxes | – | – | – | Établir |

| Cross-border cooperation | Facilitate | – | Facilitate | Facilitate |

| National competent authorities | – | – | – | Designate |

| Ressources and expertise | – | – | – | Provide |

| Cybersécurity | – | – | Ensure | Ensure |

| EU AI database | Maintain | – | – | – |

| Codes of good practice | Develop | – | – | – |

| Penalities | – | – | Implement | Implement |

| SMEs and startup | Support | – | – | Support |

3.1. DOCUMENTATION AND TRANSPARENCY

The regulation is very precise regarding the needs for documentation, quality management, and transparency of AI systems designed and deployed within the EU context.

Quality : The text emphasizes testing and validation of AI, as well as the methods and processes associated with AI design, validation, and risk management. It places even stronger emphasis on the existence or implementation of a data management process.

Transparency : AI systems require large amounts of data, both for their design and their use, and the need for reproducibility of results and observability of AI behavior appears explicitly and implicitly throughout the text. The transparency obligations set forth contribute to this: everything that can help reproduce, monitor, or interpret an AI system is indicated as part of the information to be provided to notified bodies for CE marking.

Among the transparency obligations, some relate specifically to the AI’s characteristics: its purpose, accuracy, potential risks, explainability, performance, the type of input data, the test datasets used for its design/validation, as well as information on how to interpret the AI’s outputs. Notably, the information to be provided includes a cybersecurity aspect (related both to the AI itself and to its associated datasets) and a section on AI-specific vulnerabilities.

Based on the transparency requirements, there is a strong intent to require all stakeholders to maintain control over what AI systems are and what they do.

In certain specific cases for deployers and providers, when AI-generated data is likely to be “consumed” by people, those individuals must be informed that they are interacting with or exposed to AI, up to and including the requirement to add a watermark to the produced data.

It should be noted that the text explicitly mentions exemptions from liability and documentation for AI systems when they are so-called “open-source” models.

3.2. REGULATORY SANDBOXES

If the summary provided in this article was not clear enough on this point, the regulation imposes many actions on the stakeholders of AI systems. The EU is aware of the challenges posed by this regulation and proposes what it calls “regulatory sandboxes.”

These sandboxes will be physical, software, and regulatory environments set up by national authorities to support designers, providers, deployers, and manufacturers in bringing the AI systems they offer into compliance. This would notably include making available anonymized datasets that can be used for training or validating AI systems, as well as real data guaranteed to comply with applicable laws.

The purpose of these sandboxes is to accelerate the CE marking of AI systems: an AI developed and/or validated within the framework of a regulatory sandbox would already be, by default, compliant with a certain number of articles of the regulation, thereby making its path to compliance significantly easier.

3.3. ENTRY INTO FORCE

The timeline provided by the European AI law is as follows:

- 2024-07-12: publication

- 2024-08-01: Official entry into force

- 2025-02-02: Chapters I and II concerning prohibited AI, high-risk AI, systemic risk AI, and AI awareness become applicable. [This is the current moment as this article is written]

- 2025-08-02: Most of the text applies, except Article 6(1) and Annex I. This means that other sectors (automotive, marine, rail, energy supply, etc.) that wish to use AI in their systems and products will have an additional deadline to achieve compliance (August 2027, see below)

- 2026-08-02: High-risk AI already on the market before the regulation’s publication and significantly modified must become compliant

- 2027-08-02:

- Article 6(1), Annex I applies (use of AI in products covered by other European regulations such as motor vehicles, aircraft, toys, etc.)

- General-purpose AI placed on the market before 2025-08-02 must comply

- 2030-08-02: High-risk AI already on the market and significantly modified must become compliant, in the specific case where the provider is a public institution or authority

- 2030-12-31: Large-scale AI systems placed on the market before 2027-08-02 must comply.

In summary, “pure” AI systems must be compliant by the second half of 2025, while products embedding AI for a specific function have until the second half of 2027. The Commission also provides a grace period of similar length for AI systems developed before the official publication of the final text.

For entities failing to comply, the text indicates penalties of up to a percentage of turnover (7%), adapted to the circumstances of non-compliance.

CONCLUSION

- Safeguards must be put in place. Examples of harmful uses of AI abound, and this text aims to prevent them.

- AI is a driver of innovation. While harmful uses must be prevented, it would be a shame to miss out on what AI can offer. The text acknowledges this by making specific provisions for small and medium-sized enterprises, startups, and open-source models.

- In terms of oversight and support entities, everything remains to be built: What form will the notified bodies, notifying authorities, regulatory sandboxes, and expert panels take?

USE CASES

General use cases

- I use an AI like those talked about in the mainstream media for my own personal use

- Nothing specific to do, however you will be entitled to expect and request more documentation and transparency from the provider of this AI system

- I am part of an IT department, I have authorized access to a general AI in the cloud for my company’s employees

- Nothing specific to do, you can ask the provider for more documentation, as well as support for monitoring the AI system in the context of its use by your company

- I am part of an IT department, I’m wary of the cloud, I prefer to host an AI model on my own servers for use by my company’s employees

- In this case you are considered a deployer and must comply with the obligations attached to this role in the AI regulation

- I am in the R&D department, I took an AI model and adapted it to my needs

- You are considered a provider

- I am a researcher, I invented a new general-purpose AI model…

- You are considered a provider, and you should expect to provide support to help classify your AI system

- …but I release my model as open-source

- You are still considered a provider, but will have slightly fewer obligations to fulfill because the model is open-source

- I develop a product, I use AI to assist me in writing the software that will be embedded in the product

- This is one of the most common use cases nowadays. Regarding the AI regulation, there is nothing specific to do. However, if your product category is subject to other regulations besides AI, you will need to consider the compatibility of what the AI produces for you with these other regulations, see next section for a discussion on this topic

- I develop a product in which I plan to embed an off-the-shelf AI (for example, an image recognition system)

- You must determine which category this AI falls into (prohibited, high-risk, systemic risk)

- Since you are taking this AI “off-the-shelf,” you are considered a deployer

- Your sales team will have the role of distributor

- If your clients in turn use your product as a base component to design their own product, they will be considered distributors under the regulation

- I develop a product in which I plan to embed an AI that I designed or took off-the-shelf but adapted to my needs

Use cases subject to other regulations

A common use case is the use of AI as support for activities, without the AI actually being part of the final product. For example, AI may have been used to write documentation for a project, or to write software code. In such cases, all AI outputs remain subject to the regulations, norms, or standards applicable to your product, and will be examined in light of those norms. There are two schools of thought to consider:

- AI as a software tool

- LAI as a human with certain particularities and limitations:

- An extensive knowledge of many subjects, but

- Unable or almost unable to reason

- Likely to lie to compensate for its lack of knowledge on specialized topics (the famous “hallucinations” of AI we often hear about)

A bit like a human with savant syndrome who would not hesitate to lie, to push the metaphor to the limit. On reflection, the comparison with humans is fitting: when you look to hire someone to write code for your product, you don’t just pick anyone. You scrutinize their education, diplomas, past experience, and you might even give them a few tests to be sure. Why wouldn’t it be the same for AI intended to perform similar tasks? The documentation required by the AI regulation supports this idea. Based on the schools of thought above, two approaches emerge:

- If AI is considered a software tool, then you must apply the processes of the norms applicable to software used as a support tool. For example, ISO 26262 has an entire chapter dedicated to Software Tool Qualification, so the actions aim to obtain certain guarantees that the software tool does what it claims to do and does not introduce errors. Depending on the AI systems, these guarantees may be conceptually impossible to demonstrate, and this remains an active area of research today.

- If AI is considered as an unreliable human, then it is necessary to strengthen the review, verification, and/or validation steps for the AI’s outputs.

Depending on the AI model and the situation, one approach or the other will be easier to implement (if possible) and more or less costly, but it is the standard of the final system that will be the ultimate arbiter.